By Takura Zhangazha*

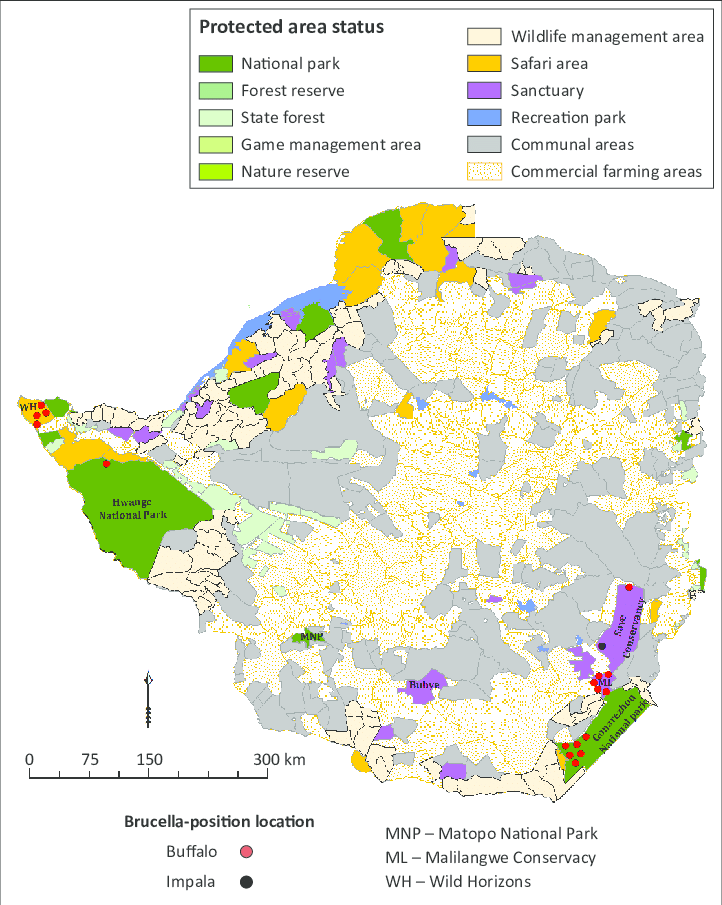

There is what should be a relatively urgent and revived “national interest” debate about land tenure/ ownership in rural, peri-urban and also former agricultural farms in Zimbabwe. This is based on the recent central government’s official policy announcing and effecting the eviction of what it considers illegal settlers on land that was allegedly distributed by village headmen with or without the approval of chiefs and rural district councils. This also includes urban councils who have also been accused of allegedly distributing land in either wetlands or former urban farms for insidious profit or political patronage.

In all of these there is reference to a common denominator called a ‘land baron’. This term did not exist in ordinary Zimbabwean political parlance before the official Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) in 2000. It also took its time to take effect in our local lingo until perhaps 2010.

It doesn’t quite have an official definition but would be generally assumed to mean that a ‘land baron’ after the FTLRP is someone with either access to political patronage within the ruling party, access to financial capital to lease or purchase state land, can or is selling and partitioning original land acquired for different uses. As acquired from the state or former white commercial farmers who were either forced off the land or sold it for a pittance at the height of the FTLRP.

Which in some cases relates to urban residential land use even if it is in a rural or peri-urban setting. Hence emergent cases of forced evictions on the outskirts of Harare, Bulawayo, Masvingo, Chipinge, Mutare, Gweru and Gutu.

The key element to bear in mind is that the centre of all these newfound evictions is based on central government proclaiming illegality of settlements after the FTLRP. Not just as a political, historical, and liberation struggle based radical nationalist policy. But as one that relates to the political economy of land and belonging in contemporary Zimbabwe.

Complicated arguments

This is a somewhat complicated argument to make. The meaning of land and land ownership (especially as capital) appears to have shifted from its historical connotations that related to historical identity and arguments about dispossession.

What has been happening since the FTLRP began and was assumedly completed is that ‘land’ has become a ‘business’. In a holistic sense. Particularly land acquired with or without government approval after 2000 to present.

If you go to any major city or emergent town, land ownership is key to urban development. Add to this either emergent agricultural mechanization programmes as led by government and related agricultural and mining entrepreneurship, you may come to conclude that ‘land’ in Zimbabwe is now essentially viewed as short and long term “capital”. In a post-colonial and newer economic neo-liberal sense.

Whereas before the FTLRP we decried white monopoly capital ownership of land, now we have a replacement but highly politicized system of ownership of the same. Admittedly it has a sense of “black empowerment’ but one that is complicated by assumptions of mimicry of its predecessor. And again because it is mainly based on a system of capitalist accumulation, it appears to be leading toward a system of displacement coupled with an asymmetric control of the majority poor and their urbanized material desires. Even if they are in rural areas.

Question over the original meaning?

That’s why when we are witnessing destruction of houses or evictions of comrades who have lived in certain areas for the last twenty years and are now being forcibly evicted for allegedly legal reasons we have to re-ask the ideological meaning of the initial FTLRP.

It would appear on the face of it that while benefitting and fulfilling a liberation struggle expectation it is now more complicated for our political economy. This is because the ‘open for business’ policy of government has now meant that land ownership and in particular as ‘capital’ cannot be open sesame or simply related to the liberation struggle values and objectives.

The courting of mining, agricultural and ‘private city investors’ means that those that were initial beneficiaries of the FTLRP face greater insecurity of tenure on the land that they had initially assumed they ‘deserved’. Historically or by way of political or economic patronage.

Especially where and when it concerns the ‘infrastructure development’ thrust of the current government. Even if they are war veterans or ruling party supporters or just ordinary people that really needed a place to call ‘home’. Hence the continually unfished story of Chiadzwa in Manicaland or Lupane as examples.

I will end with an anecdotal conversation I once had with my brother about the future of our rural homes in Bikita, Masvingo when we were much younger. The issue was whether it would be preferable to ‘urbanise’ Bikita or modernize it while retaining the communal system of land tenure. We sort of agreed on modernization while retaining traditional values and ethos of what we knew was essentially a ‘reserve area’ as the Rhodesian government deliberately designated it. Our ancestors had been displaced from the Save Valley, Chipinge and Chimanimani. Others were eventually forcibly displaced further to Gokwe.

Privatising communal rural land

In that University conversation, we argued and agreed in part that privatizing communal rural land was never going to be a good idea. Based on the experiences of what we had read about Nigeria and Kenya after their independence and what had happened with attempts at giving title for what was originally communally owned land. Even if it had been originally been designated by British and/or settler state governments.

In any event, as Zimbabweans must debate the full and realistic political economic meaning of what was the FTLRP. It took away what was once private capital and nationalized it. Many celebrated this. It is however now in a state of flux wherein the state/government is approaching it in a hybrid private/public format and outsourcing it as domestic capital for mines, carbon credits and eventual trickle down agricultural investments.

What is increasingly self-evident is that we still do not have an organic sense of what the land we took must be used for except where and when it is part of mimicry of what we overcame/ overthrew and assume to be land use success.

*Takura Zhangazha writes here in his personal capacity (takura-zhangazha.blogspot.com)

http://takura-zhangazha.blogspot.com/2024/02/a-needed-criticality-of-new-narratives.html

Related content:

Do you want to use our content? Click Here