On Saturday, March 12, police barred the opposition Citizens’ Coalition for Change from holding a rally and a procession in Marondera.

In a statement on Monday, March 14, police spokesperson Assistant Commissioner Paul Nyathi accused the party of not following regulations under the Maintenance of Peace and Order Act (MOPA), which governs public gatherings.

He said: “Firstly, it is the responsibility of a convener to notify the local regulating authority who is the Officer Commanding a Police District, of the intention to hold a rally in line with provisions of the Maintenance of Peace and Order Act (MOPA), Chapter 11:23. It is not just a case of notification, the convener has a responsibility to discuss and agree on the security and safety measures to be availed at the rally for the benefit of the public and the community in general.”

But what does this law really say?

Gathering notification

According to clauses 6 and 7 of MOPA, an organisation planning a demonstration or a march must appoint an official convenor and notify the police seven days before the event. A notice of five days is required before a public meeting. The convenor must give police details of the event, such as; the contact number of the designated convenor, the venue, times, purpose of the event, the number of marshals, and the anticipated number of participants.

If the convenor of the gatherings does not give this notice, they can be charged and fined or jailed for up to one year.

Do convenors have to ‘consult’ police?

According to police spokesman Nyati’s statement, a convenor must also hold discussions with police.

He said: “It is not just a case of notification, the convener has a responsibility to discuss and agree on the security and safety measures to be availed at the rally for the benefit of the public and the community in general.”

What does MOPA say about this?

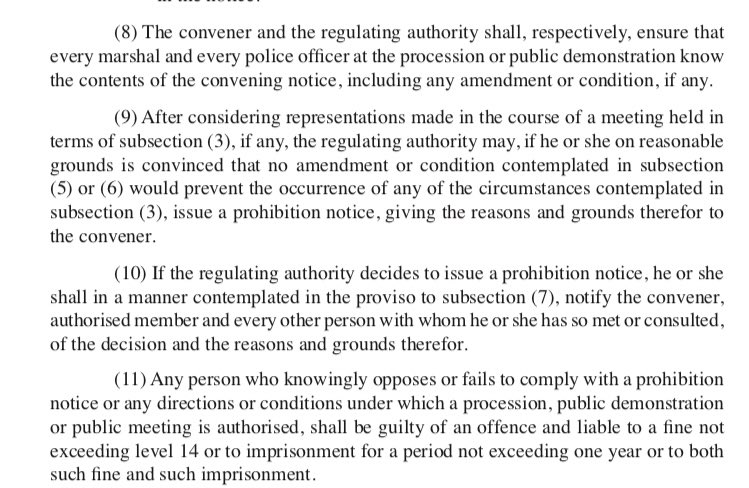

According to clause 8, if the police “receives credible information on oath that there is a threat” that the gathering may result in problems – such as violence, traffic disruptions or damage to property – they shall call the convenor to a meeting “to explore options to prevent the threat”.

At such a meeting, the convenor and police will discuss amendments to the notice of the gathering. If there is no agreement, the police can impose conditions on how the event is to be held. The clause gives the police power to ban the event, via “a prohibition notice, giving the reasons and grounds therefore to the convener”.

This prohibition order can only be given when the police have reason to believe that even imposing conditions on the event would still not be enough to prevent problems such as violence or traffic disruptions.

How does this law compare with laws elsewhere?

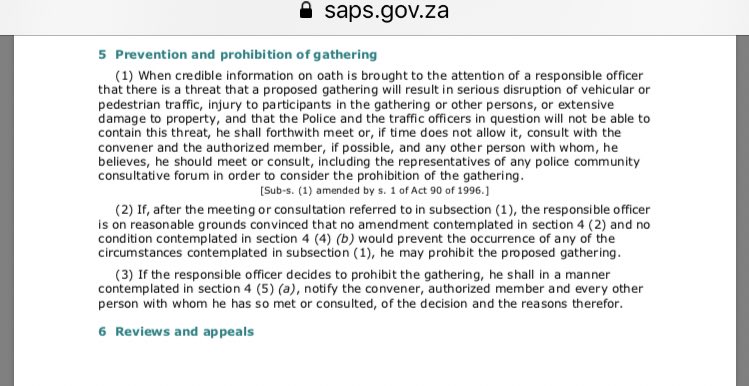

The MOPA borrows heavily from South Africa’s Regulation of Gatherings Act, to the extent that sections of the two laws are similar, almost word-for-word.

The South African law also requires conveners of public gatherings to give the police advance notice; seven days in for marches or demonstrations, and five days for public meetings such as rallies.

However, a major difference is that, in 2018, South Africa’s Constitutional Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to criminalise the failure to give notice of a gathering. The court found that this sort of penalty unfairly punishes both the convenors and the participants.

In the UK, under the Public Order Act, organisers of marches must give notice to police. Organisers can be arrested for marching without a notice or for changing the terms of the notice, such as gathering at a different time than they notified. Police can also ban gatherings if they have reason to think they may turn violent.

Are these laws constitutional?

While MOPO is similar in many respects to laws elsewhere, including South Africa and the UK, critics point out that police in Zimbabwe apply the law unevenly, frequently shutting down opposition rallies while allowing ruling ZANU PF gatherings to go ahead undisturbed.

While South African police have previously shut down some protests, opposition parties there are free to organise.

Legal experts also say ZRP’s reasons for banning opposition protests do not meet the thresholds demanded by the Constitution. According to legal experts Veritas, limits on public gatherings must only be necessary.

“While laws may limit the freedoms, the limitations must be ‘fair, reasonable, necessary and justifiable in a democratic society’ [section 86 of the Constitution]. Note that word ‘necessary’: it is not enough for a limitation to be reasonable or justifiable ‒ it must be necessary in a democratic society. If it is not, it is unconstitutional,” Veritas says in a note on MOPA.

Do you want to use our content? Click Here