There is an ongoing debate about sexual and reproductive rights in Zimbabwe.

This debate is being led by the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health and Child Care, as well as civil society organisations working with adolescent girls and young women (AGYW), which are calling for the removal of age restrictions on access to reproductive health services.

The debate has not been without controversy. Earlier this year, Parliament’s Portfolio Committee on Health and Child Care was forced to clarify its position on this issue after it was misinterpreted as a call to lower the age of sexual consent to 12 years.

On Wednesday 16 October 2019, nine CSOs – the COMPASS, YAZ, ZYT, SafAIDS, PITCH, SAT, Rutgers and ACT – took out a full-page advert in a national newspaper to lobby for the review of current legal and policy provisions limiting access to reproductive health services by adolescents.

What are sexual and reproductive health rights?

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), sexual and reproductive health rights

“encompass efforts to eliminate preventable maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity, to ensure quality sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptive services, and to address sexually transmitted infections (STI) and cervical cancer, violence against women and girls, and sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents. Universal access to sexual and reproductive health is essential not only to achieve sustainable development but also to ensure that this new framework speaks to the needs and aspirations of people around the world and leads to realisation of their health and human rights.”

Current legal and policy provisions on sexual and reproductive health services in Zimbabwe:

Although Section 76 (1) of the Constitution of Zimbabwe states that: “Every citizen and permanent resident of Zimbabwe has the right to have access to basic health-care services, including reproductive health-care services”, existing legal and policy guidelines limit access.

The Public Health Act of 2018 is not particularly explicit, but its Section 35 has been read to provide that children – defined as persons under the age of 18 – require parental or adult consent to access medical health services.

According to Justice for Children, at least two laws qualify children’s access to medical services. The organisation added that these provisions have been used to give legal backing to the established practice, that a minor under 16 years old cannot access sexual and reproductive health services and treatment without parental consent.

Section 52(2) of the Medicines and Allied Substances Control (General) Regulations, 1991, Statutory Instrument 150 of 1991 (made in terms of the Medicines and Allied Substances Control Act [Chapter 15:03]) provides as follows:

“No person shall sell any medicine to any person apparently under the age of 16 years —

(a) in the case of a household remedy or a medicine listed in Part I of the Twelfth Schedule, except upon production of a written order signed by the parent or guardian of the child known to such person;

(b) in the case of any other medicine not referred to in paragraph (a) except upon production and in terms of a prescription issued by a medical practitioner, dental practitioner or veterinary surgeon.”

Justice for Children adds that Section 76 of the Children’s Act [Chapter 5:06] presupposes that consent is a prerequisite.

This provision requires an order to be made by a magistrate, where the parent or guardian has unreasonably refused to consent to medical treatment or surgery of a minor child.

Added to this, the National HIV Testing Guidelines of 2014 state that a child under the age of 16 is unable to consent to HIV testing and counselling (HTC).

Consent confusion:

The limitation of access to sexual and reproductive health services to persons above 16 years of age is often linked to the age of sexual consent, which in Zimbabwe is set at 16 by the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform).

The notion is that a person under the age of 16 cannot legally have sexual intercourse and, therefore, can only access SRHS without a police report or adult company.

This, however, disregards the fact that Zimbabwe does not penalise consensual sex between children aged 12 and 16.

Section 70(2a) of the Criminal Code reads:

“Where extra-marital sexual intercourse or an indecent act occurs between young persons who are both over the age of twelve years but below the age of sixteen years at the time of the sexual intercourse or the indecent act, neither of them shall be charged with sexual intercourse or performing an indecent act with a young person except upon a report of a probation officer appointed in terms of the Children’s Act [Chapter 5:06] showing that it is appropriate to charge one of them with that crime.”

Given the above, Justice for Children argues:

“Because a child under the age of 16 years cannot legally consent to sexual intercourse at law, it is then presumed that a child under the age of 16 years does not need contraceptives or other SRHS, which is a belief that prejudices children.

This is because children between 12 and 16 years can among themselves have consensual sexual intercourse without offending any penal provision. That legal position aside – and most children are in fact not aware of that legal position – it is fact that children are engaging in sexual activity among themselves at early ages. Such children require access to sexual and reproductive health services as an intervention.”

In Zimbabwe, the push to remove age restrictions from access to sexual and reproductive health has been conflated with the lowering of the age of consent.

This confusion is compounded by the government’s stated intention to raise the age of sexual consent from 16 to 18, in line with the constitutional provision that only people aged 18 and above are allowed to marry.

The conflation of sexual consent and the age of marriage, informed by cultural and religious attitudes, is evident in the government’s position on the matter.

On 17 May 3018, Justice Minister Ziyambi Ziyambi told senators:

“We are saying children at the age of 16 can consent to sexual activities, yet, contrary to that it (the Constitution) says, when they are under 18, they cannot marry, so there is a contradiction. As I said, this is what we are looking at since I said we are analysing the law and we want to align this with the pending situation because it is ironic to say a child may indulge in sexual activities but cannot be married.”

Key statistics:

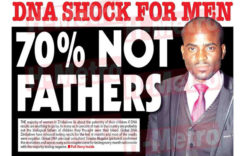

Citing various sources of data, the consortium of CSOs working on AGYW rights estimates –

- That the 15-24 age group population of girls and young women (AGYW) is 1.365 million.

- HIV prevalence for the 15-24 AGYW demographic is around 7.04%.

- In Zimbabwe, 22% of adolescent females aged between 15-19 years have begun childbearing.

- 1 in every 6 teenagers (17%) has given birth and another 5% are estimated to be pregnant with their first child.

- The proportion of girls aged 15-19 who have begun childbearing increases with age, from 3% among girls aged 15 to 48% among 19-year-olds.

- 48% of young people in Zimbabwe do not know their HIV status as they need parental consent for testing.

- 16,000 new HIV infections are attributed to young women who have never been married.

- 70,000 illegal abortions are performed in Zimbabwe annually, many of the involving adolescents under 16 years old.

In a ministerial statement given in Parliament on 8 December 2016, the then Minister of Primary and Secondary Education, Lazarus Dokora, said 4,500 boys and girls in Grade 7 would not proceed to Form 1 the following year due to pregnancy and marriage.

What are the CSOs advocating?

- The removal of age restrictions in accessing reproductive health services by adolescents, to enable them to access prevention tools which protect them from new HIV infections, AIDS related deaths, unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions.

- That adolescents be given full rights to access reproductive health information, education and services, irrespective of their age, without parental consent.

- That the age of consenting to sexual activity and the minimum age of marriage should not be linked to the age at which adolescents can access sexual and reproductive health information, education and services.

Do you want to use our content? Click Here