In a world of pandemics, rapid technological advances and unexpected climate shifts, journalists need to rise to the occasion and effectively assist intervention efforts from a position of knowledge and professional skill

By Ray Mawerera

“Our reporters need refresher courses in basic English!”, veteran Zimbabwean journalist Miriam Sibanda declared at the beginning of May. She was venting her observations to peers on a journalists’ WhatsApp social media group platform.

The cause of Sibanda’s distress was the use of the pronouns “he” and “she” in the same sentence in reference to one individual named in a story of alleged conflict between two politicians. There was a spirited defence from a colleague associated with the online publication, but happily the offending sentence has since been corrected.

That does little to detract from the gravity of Sibanda’s observation, which has been the subject of debate among professional journalists, “old school” and “new school” alike. Their chat group in question is a very vibrant platform where debate rages and dissipates and ebbs and flows occasionally, sometimes getting quite heated and emotional. Nothing is sacrosanct and debates revolve around everything from politics and economics to sports, religion, entertainment and anything else in between.

Every once in a while, the journalists train the spotlight on themselves and the “back-to-basics” argument – whenever it comes (and it does so often) – covers everything from good writing to the ethics and standards of the profession. One such debate on ethics culminated in a hastily-arranged workshop to deliberate on corruption in the media — commonly called “the brown envelope” phenomenon – at which leaders in the profession who were on the panel agreed that, since it was difficult to prove, it was a subject left well alone. It is unfortunate that the key debaters who had voiced strong viewpoints during the WhatsApp exchanges were absent from the workshop, which featured mainly young freelancers whose participation was minimal. I hope another workshop to discuss the broader issue of ethics and standards is arranged, this time giving professionals ample leeway to prepare and also opening up the composition of panellists.

The major point of this opinion piece is to revisit the whole thinking around the “back-to-basics” principle. In doing so, I know I am going to traverse areas to do with professionalism and ethics. It is unavoidable but I hope that we won’t, in the process, conflate issues and unwittingly muddy the waters.

“Abbreviation-ism”: A Generational Problem?

Isn’t it ironic, though, that what we think in our journalism profession as a serious problem affecting the way the discipline is practiced these days, turns out to be a problem across practically every other calling? It gets one thinking that it could be a function of generational shifts and technological advancement that has resulted in what some have seen as a cutting of corners and deliberate disregard for just doing things properly. I have given it my own term: abbreviation-ism.

While sharing his frustrations with today’s crop of lawyers during an informal get-together at which I was present a few weeks ago, one Zimbabwean legal guru told the group that many new lawyers were unable to prepare basic heads of argument, and were also simply at sea in writing coherent sentences.

“And that’s before we even get to professional standards!” he moaned.

As if to corroborate, Steve Mintz writes in a 2012 blog titled “New hires fail to meet expectations for professionalism in the workplace” that the problem is evident with workplace-bound college graduates, who may be victims of a social media culture where everything is abbreviated.

“In my opinion what is missing from today’s workplace-bound college students is a strong work ethic… Oral and written communication suffers from the social-media-driven culture. Recruiters tell me all the time that hires can’t write an effective memo,” he writes.

Jack Coulehan, MD, a US medical expert, suggests in his 2015 essay Today’s Professionalism: Engaging the Mind, But Not the Heart that the problem may actually emanate from the classroom. He proposes what he calls a narrative-based approach, which addresses the tension between self-interest and altruism.

There is quite a body of work on the topic of professionalism. The upshot of it is that, as broad as the term is, it tends to affect many other values that fall under that umbrella, resulting in vices that include carelessness, lack of ethics, negativity and a generally prickly attitude towards being corrected.

Worrying ageism trends

This presents a problem especially for those who would want to mentor younger professionals. A colleague told me that he detected increasingly worrying trends towards “ageism”, which is not very helpful and is, in fact, quite discouraging to would-be mentors.

The spectre of ageism, my friend said, has resulted in well-meaning veterans pulling back and withdrawing into shells that only serve to perpetuate an increasing slide into unprofessionalism.

“While creating room for employment for coming generations there is need to retain certain skills and experience,” says my friend, himself a renowned practitioner and trainer of journalists.

As examples he points to global newsrooms that feature a healthy mix of young practitioners with their more experienced counterparts. In today’s reality, however, we are sometimes ill-advisedly persuaded to literally dump skills for convenience, thereby creating yawning gaps in the way specialised subjects are tackled and reported. We see these gaps – in business and financial reporting, in stories on mining and oil exploration, climate change and in general research, the necessary bane of every news report. On the social and humane side, we see worrying tactlessness exposed in the way sensitive subjects are covered, such as coverage and protection of children, such as attitudes towards the socially indigent, marginalised or physically disabled. There is a thin line now between the supposedly professionally-trained journalist and the so-called citizen journalist, where someone thinks having a camera gives license or broadcasting rights for anything and everything.

Says Bruce Tulgan, in a 2018 blog headlined ‘The Soft Skills Gap – The Missing Basics of Professionalism:’ “Communication practices are habits, and most young people are in the habit of remote, informal, staccato and relatively low-stakes interpersonal communication because of their constant access to smartphones and social media.”

These are matters that some senior practitioners, myself included, have tried to address, either privately or through existing vehicles but the initiatives have not been successful. At one point I was advised that the journalist who already has a name and is now regarded as “award winning reporter” might consider it demeaning to take refresher courses, unless the programme was rebranded with fancy-sounding titles!

The case for getting the basics right

I still believe, however, that there remains a strong case for both back-to-basics media training (under whatever guise) and strong peer mentoring by experienced senior practitioners, if concerns by professionals like Sibanda are to be addressed effectively. There is enough interest in the improvement of media skills to make this a reality. In any case, there is a global expectation that all professionals – and journalists are right up there with the most critical of them – should at least get the basics right. Those basics, for the journalist, must today include the new forms of fact checking, verification and basic research that form an integral part of story compilation.

Then, of course, there is the small matter of writing skills. Time was when newspapers were a go-to source of examples on how to write. These days we are assaulted by bad use of idioms, bad spelling, poor grammar and annoying carelessness that all, somehow, pass the scrutiny of editors at every level to become the butt of jokes when they hit the public domain. This must be addressed.

Journalists must also tackle subjects that they know something about, if not thoroughly well then at least well enough to assist the reader. We know from the reality on the ground that our colleges do not offer any meaningful specialisation training, which compels institutions employing media practitioners to invest in programmes to produce their own ideal worker. An intervention at college level may be justifiable, perhaps borrowing and creating an appropriate adaptation from Dr Coulehan’s narrative-based approach (that is, addressing self-interest-based attitudes together with professional standards and ethics).

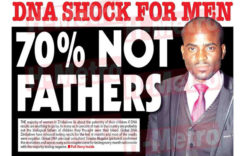

When faced with global pandemics that may be puzzling to appreciate, good journalism rises and takes up such matters, reporting accurately and faithfully. The current environment suggests this is not always the case, because the individual journalist is not appropriately capacitated. There is a tendency to take the easy way out and this, unfortunately these days, sometimes includes picking up threads from untrained activists on social media. Apart from the damage that that does to social growth and development, it cheapens journalism.

Media must grow in tandem with national growth

These are challenging times with serious paradigm shifts in the way and speed the world is evolving. The media in any country needs to grow as the country grows and it is my strongly considered view that there is a crying need to focus on professional training and mentoring – journalism and the whole sector of the communication and information dissemination industry are the fuel that drives the engines of development and growth.

We must be wary, of course, of the need to balance our world view with how those we think have become less professional also look at the entire subject, as affected as it is by technological advances that have created a completely transformed environment. Getting traction in training and mentoring depends on mutual understanding and appreciation of the common vision and objective.

Tulgan: “Much of what older, more experienced people might see as matters of professionalism – such as attitude, self-presentation, schedule and interpersonal communication – are what young adults are more likely to consider personal matters of personality, style or, which are none of their employer’s business.”

Zimbabwe media needs to go back to basics to improve journalism and its role in society.

Ray Mawerera is a veteran journalist, branding, communications and public relations expert who has worked across Zimbabwe’s media and business sectors from the 1980s. He chairs the boards of a number of organisations.

He wrote this opinion piece as part of his contribution to efforts towards developing the media in Zimbabwe.

Do you want to use our content? Click Here