The following is a paper presented by ZimFact Editor-in-Chief Cris Chinaka at the Zimbabwe New Media Summit, hosted by the NUST American Space at the National University of Science and Technology on July 18, 2019:

By Cris Chinaka

On the eve of a big battle with Afrikaners in 1876 over land, one frustrated but still hopeful African warrior chief woke up in the dead of the night and prayed:

“Oh Lord!

Despite many prayers to You, we are continuously losing our wars.

Tomorrow we shall again be fighting a battle that is truly great.

With all our might we need Your help and that is why I must tell You something:

This battle tomorrow is going to be a serious affair.

There will be no place in it for children.

Therefore, I must ask You not to send Your Son to help us. Come Yourself.”

(Quotation from the novel, Another Day of Life, a tale of the birth crisis of independent Angola by Ryszard Kapuscinki)

The spread of false news and information largely through digital platforms has become an overwhelming global crisis.

The phenomenon of false news and information that many today simply call “fake news” arises from the dissemination of misinformation and disinformation by individuals or organized groups seeking to advance some agendas.

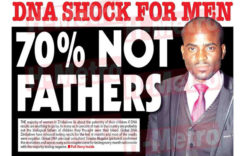

The information landscape gets polluted daily by people committed to subverting facts in order to influence audiences in certain directions.

The news and information ecosystem gets polluted by people who have little- to no- care on whether they are disseminating verified or false information.

The problem has been heightened by a fall in public trust in the mainstream media globally, the use of and increasing reliance by many people on social media as their main source of news and information – including platforms where this information is unverified.

Low quality journalism is not helping the case.

The fall in trust in the media by the public invariably extends to lack of trust in politicians.

A 2018 annual survey by Ipsos MORI shows that people don’t trust politicians, ranking them second from bottom just above advertising executives in the public’s trustworthiness of professions. The politicians were associated with negative perceptions and words such as contemptible, disgraceful, parasitical, sleazy, traitorous.

This is telling as politicians and public officials are internationally regarded as the major sources of news and information given to problems of distortions.

The British weekly Economist magazine recently commented that: “Regardless of their abilities, political leaders have to perform before an increasingly hostile audience which routinely questions their motives and trashes their achievements.”

It argued that this loss of confidence in leaders has sparked a surge of “know-it-all cynicism” and “the politics of resentment” on the one hand, and on the opposite, “inchoate enthusiasm” by followers who don’t doubt or question their leaders.

Where are we?

Zimbabwe’s media space is largely a political battlefield.

It is a frontline where fierce fighting is taking place between rival politicians, backed by both enlisted and volunteer forces of media trained and untrained supporters.

The criticism that we collectively face in the media is that we lack a sense of balance and fairness in our coverage of issues.

The general observation is that our highly polarised national politics feeds into a media space where there are sadly slavishly pro-government anti-opposition players and rabidly anti-government pro-opposition media activists.

Many people believe that our media is sucked in sledgehammer political propaganda in which factual reporting takes second place to pushing opinions dressed as “news stories.”

Outside these, both the governing ZANU-PF party and the main opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) organization have cyber-warriors in their ranks churning out propaganda through commentaries on “real news stories”, gossip and planting misleading information.

Studies around Fact-Checking a society and sector where people have taken hardline political positions is hard because in most cases there are more opinions and false information circulating in silos and echo chambers occupied by people who already share common beliefs.

It has also been proven that some people are uncomfortable about seeking information that challenges their beliefs.

So beyond fact-checking in a manner that is neutral and even handed, the global challenge is to promote media literacy for the public to appreciate the dangers of false news and disinformation and to find easy ways for people to identify the false stuff.

It’s not that easy!

In Zimbabwe’s case that danger lies in:

1. Hyper-partisan and hyperactive cyber warriors peddling opinions and political propaganda with absolutely no sense of balance and reasoning;

2. Hyper-sensationalisation and hyper-personalisation of issues.

We have to find a balance between managing fake news without stifling freedom of expression. We do this by separating Fact from Fiction, separating Opinion from Fact.

People need Facts, Correct Information to make correct decisions and to relate to issues in a balanced way.

In a world overwhelmed by social media, the value of mainstream reporting and journalism is to give meaning to news and information.

It is to demonstrate why the news and information is important to the various audiences, to Connect and Empower the people. The value is in Interpretation and Analysis. Why is this important? Where is this going? Where is it coming from?

In my view the value of professional journalism and reporting has been enhanced rather than devalued by the emergence of social media, and the mountains of information and “news” dumped on us every second.

But this requires that all of us — from our different stations in life — should support the growth and eminence of quality journalism over low-value “pedestrian grade reporting”, the “second-hand-type” of journalism that we have to deal with daily.

In our situation here in Zimbabwe, I see three practical ways in which this can done:

Firstly, as consumers of news, we must promote quality journalism by challenging falsehoods and blatantly biased reporting through the same or alternative information platforms.

Secondly, as experts, commentators, information providers, potential news sources or “newsmakers”, we must become sources of public interest and verifiable information and not the sources of shameless propaganda, misleading, false or fake news. The information should be provided in a way that is easily understandable, including in terms of the language used.

Thirdly, alongside promoting media literacy, the media itself needs continuous education to appreciate deeply some of the issues they would be reporting on.

Besides the dangers around false news and information around our politics, the other major challenge is on how the media — both mainstream and social — are reporting the economy.

How is our media covering the economy?

And to what level is the reporting based on a clear understanding of the economic fundamentals?

It is very clear that most of the economic reporting that we currently have is based on “talking heads”, on speeches, statements and commentary that make little reference to economic fundamentals or to facts on the ground.

There is a plenty of misleading news stories around the Zimbabwe economy.

Some of the make little reference to economic indicators, context and other relevant information.

While there is also some very commendable reporting around the economy, there is clearly room for more considering its importance- that economic reporting is about our welfare, our food, our bread and butter!

In simple terms, Economic Reporting is about how People are Living and how they are earning their living.

The economic fundamentals are important because they measure all these elements, but the context and background is equally important.

Our experience at ZimFact (www.zimfact.org) is that alongside capturing the economic issues and relating them to the fundamentals, the media has a responsibility to present them in a digestible manner, to break them down (to demystify), and to put them in context.

The media has a responsibility to communicate clearly and accurately, without fear of breaking down the numbers:

There is a general belief that many journalists have an inherent fear of numbers: Arithmophobia – the fear of numbers.

On the other hand, many potential news and information sources suffer from Journophobia, the fear of journalists.

Both these fears have a negative impact on reporting and journalism, the omission of critical data and information from stories.

Zimbabwe media needs to systematically include critical data and relevant information in its reporting of the economy. This requires Knowledge, Skills and Ethical Application, including investment in Financial Reporting and Data Journalism.

On the part of potential news sources, like colleagues at this Dialogue, this requires investment in media skills training.

In both cases, we need leadership.

The question of leadership is a critical issue across sectors, a hot point across the globe.

But because the media sits at the centre of other activities and is crucial to understanding daily what is happening in politics, in business and finance, in industry and commerce, in entertainment, in education, in health, in science and technology, in social life and culture, the media requires a leadership with greater skills than we generally believe.

These are skills that go beyond, but can be built on, sound academic education and technical training, to include a judicious temperament and disposition and a strong commitment to ethics and public accountability.

The challenge for Zimbabwe is to build a media leadership with a “Triple A” rating of great Aptitude, great Attitude and great Application in terms of knowledge, skill and ethics.

There are many people who argue that the media has been emotional in its approach to the Zimbabwe story, obsessively focused on partisan politics at the expense of other issues, with editors and their masters deciding almost dictatorially what the public must read or not read, hear or not hear, see and not see!

The question is how do we get a balance, and develop a system that serves democracy?

I take it that the concept of democracy in its broad sense is now universally accepted except by the most patronising or those who want to qualify it for reasons of partisan politics.

The media serves democracy when its leadership – its editors — are aware and awake to their responsibility to provide people with news and information that help them to make choices.

The leaders in Zimbabwe’s media industry must be skilled enough to deal with political and business pressure, with “masters of spin” dominating the sector and with the dangers of “brown envelope journalism”.

While social media has shifted the locus of power of news corporations, industry studies and surveys suggest that ordinary people still rely on the traditional or mainstream media for interpretation of politics, business and financial news.

People have a right to a diverse form of news and information on what is going on around them, what is not happening and why, policies, plans and programmes around their lives.

The media has a responsibility to meet this right, and that responsibility becomes almost mandatory in a country where the media industry is small, and national hopes and expectations have been undermined by both politics and the press.

That responsibility is greater on a media sector which, for years, had become a hostage of politics, and it is also greater on news makers and generators who are in other social fields.

Journalism is a key part of the knowledge industry, and its leaders must play their part and be ashamed to be associated with mediocrity.

The challenge for Zimbabwe’s media leaders and Zimbabwean journalism is to tell a full story, and failure to do so is bad journalism.

Bad journalism is failure to report accurately, fairly, comprehensively and credibly what is going on across the sectors. It is a journalism that is not creative enough to find diverse ways of conveying news and information.

The net cost of bad journalism is an uninformed or ill-informed public.

But the cumulative costs are much, much higher.

Bad journalism misinforms and misinterprets. It can undermine the credibility of organisations, programmes, plans, policies and personalities; it can breed suspicion, raise anxiety, drain public support and confidence, invite unwelcome focus on trivia or secondary issues around institutions and can cost money and development.

Bad journalism can incite conflict, create misunderstandings, and exacerbate problems.

For those of us in the media, let us help stem the flow of fake news by:

remembering that our information ecosystem is dominated by hyperactive and hyper-partisan cyber warriors pushing political propaganda which needs to be fact-checked. This includes us not becoming conduits of false news and information.

working to restore public trust in professional and mainstream media by focusing journalism on public interest issues and handling these as factually as possible.

promoting media literacy for the public to help challenge those spreading false or misleading information.

Let us all rally around this.

Do you want to use our content? Click Here