FOLLOWING the 24 August 2018 Constitutional Court decision which validated the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission’s declaration that President Emmerson Mnangagwa won the 30 July 2018 harmonised general election, opposition MDC Alliance leader Nelson Chamisa’s legal team is reportedly in the process of lodging a petition with The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR).

The lawyers are seeking to challenge the decision made by the Constitutional Court alleging that it violates the universal human rights of the people of Zimbabwe. Chamisa has refused to accept the decision by the Constitutional Court to dismiss his election petition with costs.

Title of the petition: “ACHPR PETITION CHALLENGING THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT ELECTION DECISION IN THE AFRICAN COMMISSION FOR HUMAN AND PEOPLE’S RIGHTS (ACHPR)

Grounds of the petition

Among other issues, the grounds of the petition are based on the flagrant and multiple violations of the universal human rights of the voters and people of Zimbabwe by the current Zimbabwean regime and the Constitutional Court, including:

(a) The right to free and fair elections;

(b) The right to a fair hearing before an impartial court;

(c) The right to legal representation by counsel of choice;

(d) The right against undue political interference; and (e) The right to be governed by a legitimate government.

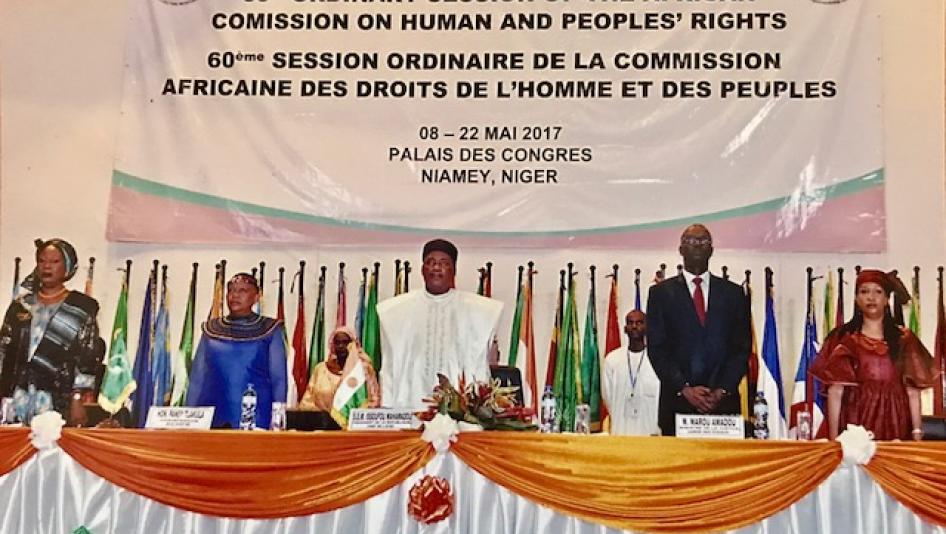

About the ACHPR

The African Charter established the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights on 21 October 1986. The African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (the African Charter) came into force, giving both hope and guarantees for the protection of human rights on the African continent after the Commission was inaugurated on November 2 1987 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. After this, the Commission’s Secretariat was subsequently relocated in Banjul, The Gambia. In addition to performing any other tasks which may be entrusted to it by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government, the Commission is officially charged with three major functions:

-the protection of human and peoples’ rights

-the promotion of human and peoples’ rights

-the interpretation of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights

Composition of the ACHPR

The Commission is composed of eleven members (Article 31 ACHPR):

- ‘Chosen from amongst African personalities of the highest reputation, known for their high morality, integrity, impartiality and competence in matters of human and peoples’ rights; particular consideration being given to persons having legal experience.’

- ‘The members of the Commission shall serve in their personal capacity.’

- Their mandates are for six years, renewable.

Zimbabwe’s ACHPR Status

Zimbabwe first ratified some provisions (not all) of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights in 1986. The southern African country is part of states that have not ratified all binding instruments.

Who can file a complaint?

On its website, the ACHPR says anyone may bring a complaint to the attention of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights alleging that a State party to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights has violated one or more of the rights contained therein. Individuals and NGOs in Africa and beyond have over the years seized the Commission with complaints of this nature. Article 55 ACHPR does not place any restrictions on who can submit cases to the Commission. This provision simply notes: ‘Before each session, the Secretary of the Commission shall make a list of the communications other than those of States Parties to the present Charter’. The Commission has interpreted this provision as giving locus standi to the victims themselves and to the victims’ families as well as NGOs and others acting on their behalf.

Admissibility

Legal experts say aggrieved African parties and citizens may only approach the ACHPR after internal domestic legal steps have been exhausted. They suggest that this is clearly the case here since judgments of the Constitutional Court of Zimbabwe are not appealable in Zimbabwe, as it is a court of last instance. Article 56(5) ACHPR. The Commission can only deal with communications if they ‘are sent after exhausting local remedies, if any, unless it is obvious that this procedure is unduly prolonged’.

Time period: Article 56(6) ACHPR. The Communications must be ‘submitted within a reasonable period from the time local remedies are exhausted or from the date the Commission is seized of the matter’.

Duplication of procedures at the international level: Article 56(7) ACHPR. The Commission does ‘not deal with cases which have been settled by these states involved in accordance with the principles of the Charter of the United Nations, or the Charter of the Organization of African Unity or the provisions of the present Charter’.

Inadmissibility

Article 56 ACHPR. ‘Communications relating to human and peoples’ rights referred to in Article 55 received by the Commission shall be considered if they: (1) Indicate their authors even if the latter request anonymity, (2) Are compatible with the Charter of the African Union Charter, (3) Are not written in disparaging or insulting language directed against the state concerned and its institutions or to the African Union.

Measures

The Commission has developed a mechanism for adoption of provisional measures in its Rules of Procedure (Rule 111). ‘1. Before making its final views known to the Assembly on the communication, the Commission may inform the State Party concerned of its views on the appropriateness of taking provisional measures to avoid irreparable damage being caused to the victim of the alleged violation. 2. The Commission may indicate to the parties any interim measure, the adoption of which seems desirable in the interest of the parties or the proper conduct of the proceedings before it.’

Settlement

Article 52 ACHPR. ‘After having obtained all the information it deems necessary, and after having tried all appropriate means to reach an amicable settlement based on the respect of Human Rights and Peoples’ Rights, the Commission shall prepare a report stating the facts and its findings.’ Rule 98 Rules of Procedure. ‘The Commission shall place its good offices at the disposal of the interested States Parties to the Charter so as to reach an amicable solution on the issue based on the respect of human rights and fundamental liberties, as recognized by the Charter.’

Guidelines for the submission of communications

The ACHPR has an Information Sheet published by the Secretariat of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Its purpose is to inform people or groups of people, and states parties to the African Charter on human and Peoples’ Rights on how they can denounce alleged violations of human and peoples’ rights within the African human rights protection system. It covers such matters as the rights and freedoms protected in the Charter, conditions for submitting communications, emergency communications, who can submit a communication, how many violations per communication, legal representation and a standard format for the submission of communications.

Written procedure, official and working languages are set out in Rule 34 Rules of Procedure of the Commission. ‘The working languages of the Commission and of all its institutions shall be those of the Organisation of African Unity.’ ‘The working languages of the Union and all its institutions shall be, if possible, African languages, Arabic, English, French and Portuguese.’ (Article 25 Constitutive Act of the AU). Website: www.achpr.org

Sessions

The Commission holds two ordinary sessions per year and may meet, if need be, in extraordinary sessions. The working languages are those of the African Union. The working sessions may be held in public or in camera. The Commission may invite States, national liberation movements, specialized institutions; NHRIs, NGOs or Individuals to take part in its session.

Items on the agenda shall deal with, inter alia, on the one hand, the consideration of complaints and periodic reports (which will be dealt with later on and on the other hand, with the examination of promotional activities and other matters as may be proposed by the various participants to the proceedings of the Commission, and especially by nongovernmental organizations.

Judgements

Article 27(1) Protocol: ‘If the Court finds that there has been violation of a human or peoples’ right, it shall make appropriate orders to remedy the violation, including the payment of fair compensation or reparation.’

- Binding force: Article 30 Protocol. ‘The States Parties to the present Protocol undertake to comply with the judgement in any case to which they are parties within the time stipulated by the Court and to guarantee its execution.’

- Execution of judgements: Articles 29 and 31 Protocol establish a role for the Assembly and Council of Ministers of the AU to guarantee compliance with the judgements: The Court shall submit an annual report to the Assembly and specify, in particular, the cases where a state has not complied with the Court’s judgement (Article 31 Protocol). ‘The Council of Ministers shall also be notified of’ the judgement and shall monitor its execution on behalf of the Assembly.’ (Article 29(2) Protocol).

Advisory Opinions

Article 4(1) Protocol: ‘At the request of a Member State of the AU, the AU, any of its organs, or any African organisation recognised by the AU, the Court may provide an opinion on any legal matter relating to the Charter or any other relevant human rights instruments, provided that the subject matter of the opinion is not related to a matter being examined by the Commission.’ The mandate of the Court in this regard is considerably broader than that of the Commission

Zimbabwe case and the outcome of the ACHPR

Legal experts say that if the African Commission makes findings that are different from the Constitutional Court of Zimbabwe judgment, those findings will not reverse the judgment of the Concourt.

The overwhelming view is that the African Commission is a quasi-judicial body which makes recommendations not judgments which are not in themselves legally binding upon the State concerned.

CONCLUSION: So the move by the MDC Alliance will at best generate recommendations which can be useful in pushing ahead the debate for electoral reforms, the legal experts say.

Factsheet by ZimFact staff

Do you want to use our content? Click Here